First published on data.unicef.org

Madhamal (left) was spared an early marriage, but her sister, Vennila (right) was not so lucky.

Madhamal, from a village in Tamil Nadu, India, had always dreamed of becoming a teacher. But that dream was shattered – at least temporarily – when her father attempted to force her to marry. Child marriage in India is illegal, and after Madhamal confided about her situation to her teacher, the wedding was called off. She went on to become the first child in her community to reach the ninth grade, and is now a role model for other young people.

Not all stories like these end happily. Each year, 12 million girls are married before they turn 18. The consequences can be devastating – and lifelong. Madhamal’s own sister, Vennila, was married at 16, and now has two children.

Child marriage is frequently accompanied by early childbearing, before a young girl’s body is ready to give birth. Early marriage and childbearing can result in physical as well as psychological harm, but they also tend to deprive girls of opportunities to fulfil their potential. Isolation from family and friends, and an end to their education, are usually the norm. Globally, the situation is grim: 9 out of 10 married girls worldwide are out of school.

Low levels of education are a defining feature of communities in which child marriage is most common. It is telling, for example, that in the five countries with the world’s highest rates of child marriage, 15 per cent or fewer girls finish secondary school; in the top three countries, completion rates for secondary school are no more than 5 per cent.

Fortunately, schooling can be protective against child marriage. Even in countries where the practice is very common, girls with at least a secondary education are often spared early marriage.

While families’ decisions about their daughters’ schooling and marriage prospects may be complex, the reality facing girls is that remaining a student and becoming a bride are typically viewed as divergent paths.

Keeping girls like Madhamal in school is among the best ways to give them a chance at a brighter future without child marriage. That said, simply being in a classroom is not enough. Girls deserve quality education that confers knowledge, builds skills and empowers girls to successfully transition to employment. Parents, it seems, already know this: Evidence shows that families who believe that girls will be able to secure good jobs are more likely to keep their daughters in school [i].

Education is also a lever against FGM

Education plays a crucial role in discouraging child marriage by presenting a valuable and viable path for girls. In a different way, education also has the power to combat another harmful practice: female genital mutilation (FGM). At least 200 million girls and women alive today have been subjected to FGM, mainly in 30 countries but also in diaspora communities around the world.

Fatima, age 15, lives in the South Kordofan state of Sudan, and has just returned from a community awareness session about FGM. “I believe FGM should stop,” she says. “Girls in my school who have been subjected to FGM have very painful periods. It is bad.” She also learned that FGM causes excessive bleeding, which be fatal. Without any pressure from her family to undergo the practice, she feels safe and relaxed. But Fatima is in the minority. In South Kordofan, 89 per cent of girls and women have undergone the procedure [ii]. Fatima’s overarching message to girls is this: “FGM will destroy your life. Don’t accept it.”

As with child marriage, education is considered a key strategy to eliminating FGM. Data show that education can be pivotal in both shifting attitudes and ultimately stopping the transmission of FGM to subsequent generations.

In the case of child marriage, school can provide a safe haven and ultimately an alternative path to marriage. But a different mechanism is at work in the case of FGM. Increasing levels of education are correlated with increasing opposition to FGM. Education, therefore, may serve to confer information about the dangers of the practice in a way that can shift attitudes about its acceptability, as in the case of Fatima. Advancing through the education system might work in more subtle ways as well, by exposing students to different cultures that do not practice FGM. Education can also foster an environment in which new ideas become less threatening and harmful traditions can be openly questioned.

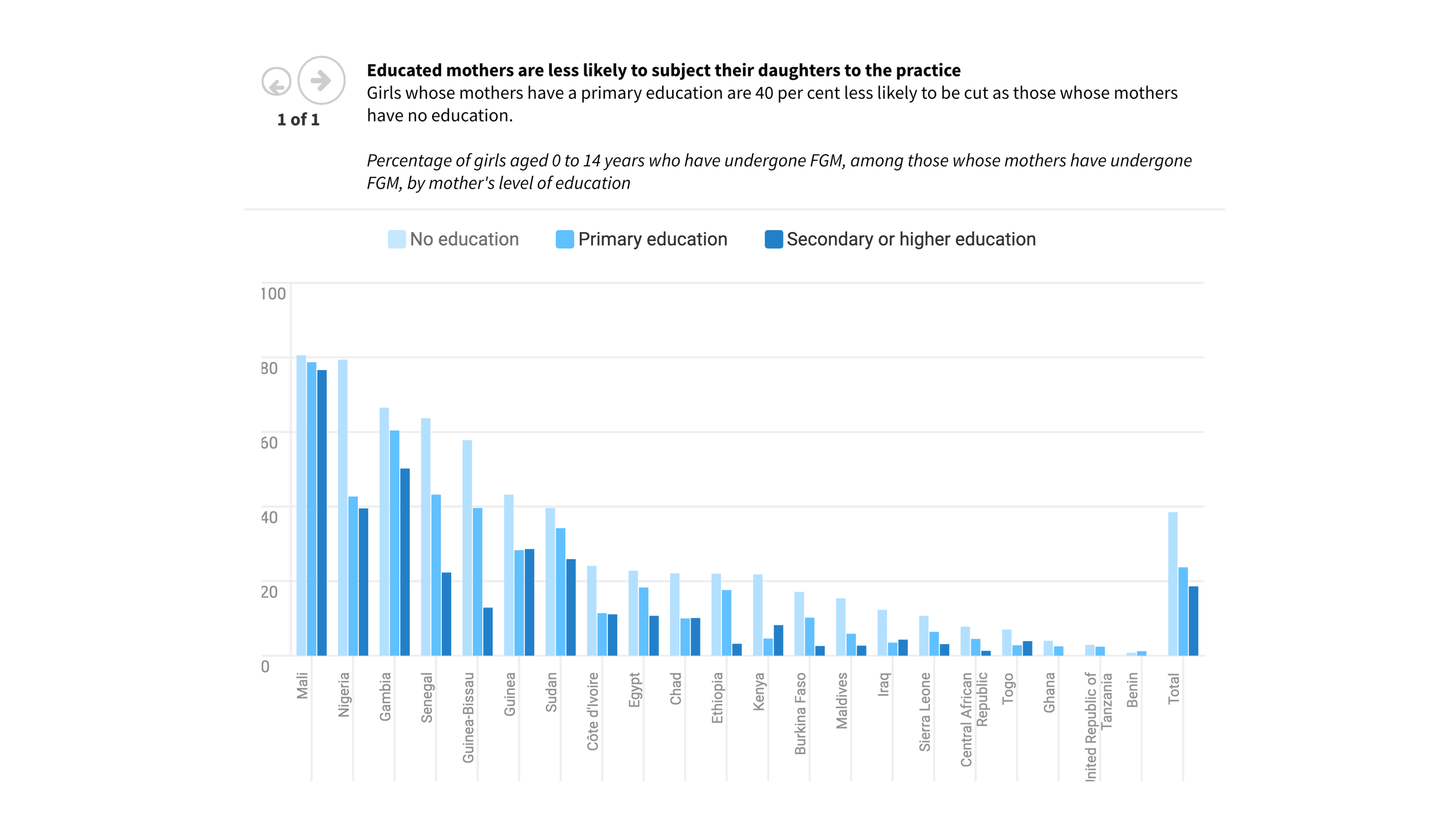

In many contexts, FGM is performed at a very young age – often before age 5 – so a link between a girls’ own education level and her likelihood of experiencing the practice is not to be expected. In places where FGM is customarily performed early in life, a girls’ FGM status is determined before she begins elementary school. However, a shift in attitude as she grows up means that she may decide not to cut her own daughters. This, in fact, is borne out in the data: Girls whose mothers have a primary education are 40 per cent less likely to be cut than those whose mothers have no education. And in many countries, women with a secondary education are even less likely to continue the practice of FGM into the next generation.

While this is encouraging, education does not systematically translate into changes in behaviours, and even some mothers with advanced education have subjected their daughter to FGM, particularly in countries where societal pressure is strong. This suggests that other social and cultural factors are at play. Education is one important tool in shifting attitudes away from FGM, but must be combined with other effective strategies to tackle the practice in places where it has proved to be highly resistant to change.

A brighter future for girls

Child marriage and female genital mutilation are both violation of girls’ human rights. As such, they have been rightfully targeted by the global community for elimination by 2030, through the Sustainable Development Goals. But to achieve these ambitious goals, more must be done to protect the rights of girls worldwide so that they have full autonomy over their own bodies and the power to determine their own futures. This includes the choice of if, when and whom to marry.

The challenge is daunting, since both practices are deeply rooted in many societies. Understanding what drives child marriage and FGM – and what tools are most effective at undermining their persistence – is key to their elimination. And this is where solid data come in.

Our recent analyses on the intersection of education with each of these harmful practices offer support for the argument that universal, quality education is one of the most powerful tools we have to end harmful practices, and to prevent them from being passed onto the next generation. For Madhamal and Fatima and millions of other girls around the world, there is no time to lose.